Learning to See Wings Differently: Bird Migration Studies at Point Calimere

A field ornithology journey with BNHS through bird ringing, conservation, and coastal wetlands.

Some journeys don’t begin with destinations — they begin with attention.

With every kilometre travelled, every question asked, and every silent observation made, the world slowly starts revealing patterns we once overlooked. My participation in the Basic Course in Field Ornithology and Bird Migration Studies by Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) at Point Calimere was one such journey — not just into wetlands and migration science, but into patience, humility, and learning how to truly see birds.

Before the first bird was counted, before the first wing was measured, the journey itself had already begun to teach me.

How the Journey Began: From a Dawn Bus to the “Kuruvi Office”

I reached Vedaranyam by bus at around 5:30 AM. The town was still half-asleep, wrapped in coastal silence, with dawn gently stretching across the horizon. From there, I began looking for a bus towards Kodiyakarai.

Before I could figure things out, an auto rickshaw pulled up.

“Enga poganum?”

“Kodiyakarai… BNHS office… forest department office near Pallivasal stop,” I replied.

The driver paused briefly, processed my city-style explanation, smiled, and translated it into local truth.

“Kuruvi office-ah? Vaanga!”

Just like that, BNHS became Kuruvi office — the bird office. It felt symbolic. Perfect, even.

My senior friend Sanjeev and I got into the auto and began our short journey. As we drove through waking villages, salt pans, and quiet roads, curiosity took over. I kept asking the driver questions — about livelihoods, local uniqueness, places of interest, and authentic food.

Patiently, he answered everything, stitching together geography, ecology, and everyday life. By the time we reached our destination, learning had already begun — guided not by slides or schedules, but by lived knowledge.

Arriving, Settling In, and the Sweetest Tea Ever

At the BNHS premises — Kuruvi office — we were allocated tents. Sanjeev and I were assigned the same one, which felt reassuring. We dropped our bags, freshened up quickly, and stepped out almost immediately.

Because the first instinct was obvious: tea.

With two fellow birders, we walked to a nearby tea shop. The tea arrived — despite clearly requesting low sugar — tasting more like payasam in a tumbler. It was unapologetically sweet, intensely local, and oddly comforting.

We laughed, sipped anyway, and walked back — warmed by sugar, humour, and anticipation.

Soon, a few more participants joined us, and without ceremony, our first birding session began. Binoculars came out, conversations softened, and Point Calimere quietly welcomed us.

Tent stay, clear night sky, beautiful morning/evening skies

The Rhythm of Life at Point Calimere

Days at Point Calimere settled into a beautiful, purposeful rhythm:

Early morning birding site visits, when the wetlands came alive

Classroom sessions, grounding observations in science

Demonstrations, where theory met practice

Afternoon field visits, revisiting landscapes with sharper eyes

Bird ringing and tagging sessions, where learning carried responsibility

Each day felt full, yet never rushed. Observation flowed naturally into understanding.

Birds That Stayed With Me

From mudflats dotted with sandpipers and plovers to the effortless glide of Brahminy Kites, the diversity was breathtaking. Quiet encounters with White-browed Bulbuls and fleeting glimpses of Blue-faced Malkohas reminded me that brilliance doesn’t always demand attention — sometimes it waits for patience.

Bird counting sessions revealed how numbers tell stories. Each count feeds long-term datasets, helping track migration shifts, population changes, and climate impacts. I learned that careful observation is one of the strongest tools in conservation.

Some birds remain with you not because of rarity, but because of the story they arrive with.

During one of our field sessions, we were quietly birding — observing storks, plovers, sandpipers, and terns, letting the landscape unfold at its own pace. That’s when our lead, Shivakumar, received a message.

Flamingoes.

Somewhere far out in the salt pans.

There was no hesitation. Binoculars went down, excitement went up, and we started moving — fast. What followed was nearly 25 minutes of brisk walking across the salt pans, eyes scanning the horizon, hearts slightly racing.

Halfway through, a local cyclist rode past us, slowed down, sensed the urgency, and joined in. In a moment of spontaneous field camaraderie, I borrowed his cycle and pedalled ahead.

Riding through salt pans on a cycle with no rear brake and a barely-there front brake was equal parts terrifying and hilarious. Dust, wind, laughter, and adrenaline — fieldwork has its own kind of joy.

And then… we saw them.

A large flock of flamingoes, heads down, rhythmically digging into the ground, their calls carrying softly across the open landscape. The salt pans glowed under the evening light, and the flamingoes seemed almost unreal — a moving wash of pink against the muted earth.

We stood there quietly, breathless — not from the walk, but from the moment.

That sunset, with flamingoes feeding freely in the distance, reminded me why we do all of this. Why we walk. Why we wait. Why we rush when needed.

Some sightings are not just about the bird — they are about the journey to reach them.

Walking the Landscapes: Forests, Salt Pans, and Shorelines

Our learning extended far beyond the classroom.

A walk through Kodiyakarai Wildlife Sanctuary revealed forest trails where land meets sea. Dry evergreen vegetation, saline winds, and subtle birdlife showcased how multiple ecosystems overlap seamlessly.

The salt pans, stark at first glance, revealed themselves as critical feeding grounds. Birds adapted, foraged, and thrived — reminding us that coexistence, when allowed, creates unexpected habitats. Observing birds forage here reinforced a key lesson: nature adapts faster than we expect, but only when space is allowed for coexistence.

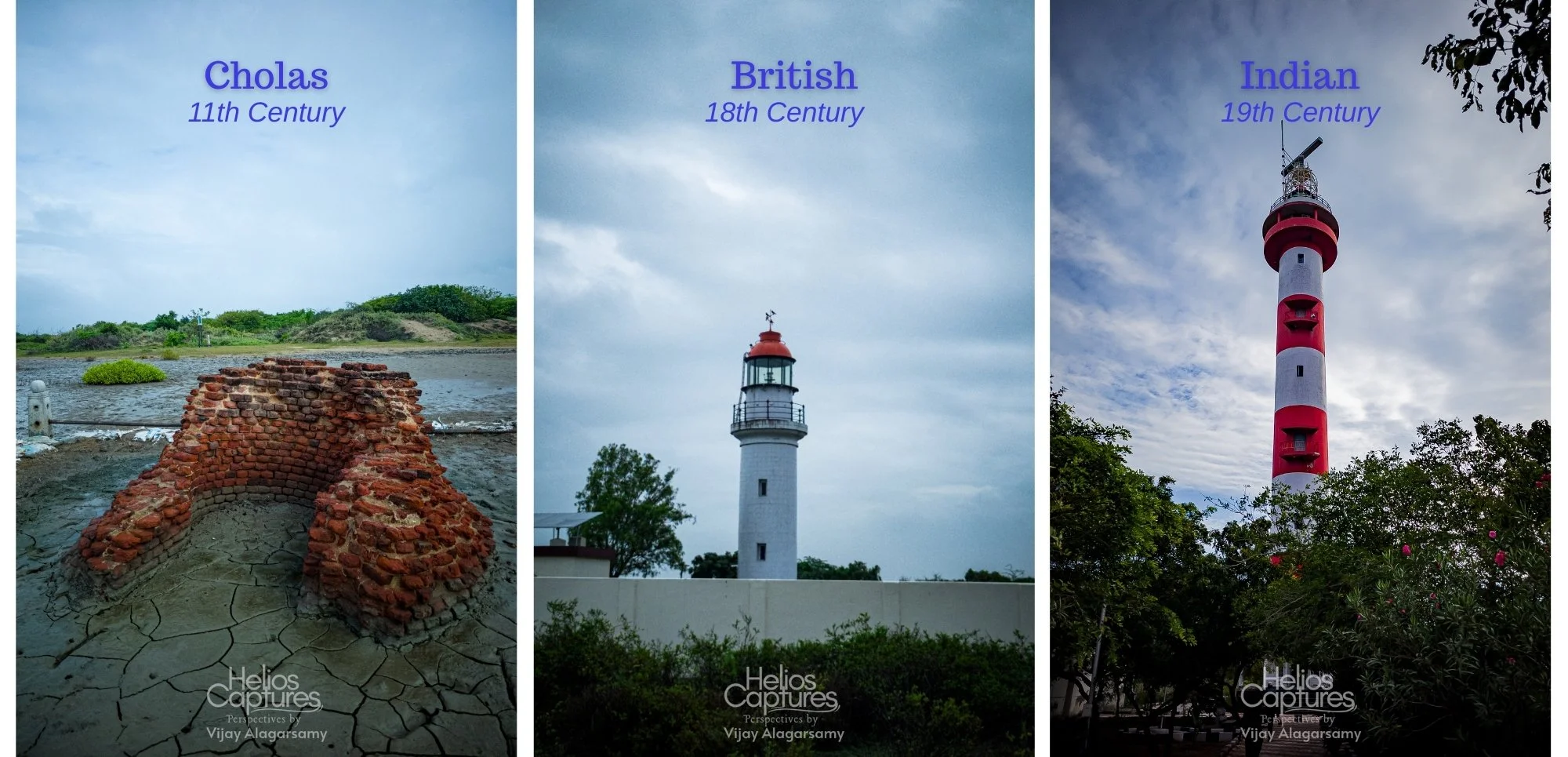

Three Lighthouses, One Migratory Coast

Visiting all three lighthouses of Point Calimere felt like walking through time — each structure standing as a silent witness to changing coastlines and navigation needs.

Chola Lighthouse

The ruins speak of an era when coastal navigation depended on fire, intuition, and deep knowledge of the sea — much like birds once did.British Lighthouse

A reminder of colonial maritime expansion, precision engineering, and the growing importance of mapped sea routes.Point Calimere Lighthouse

The present-day sentinel — automated, powerful, and functional — guiding ships while migratory birds continue to navigate by instinct and stars.

Standing there, it was impossible not to draw parallels between human navigation systems and avian migration — both shaped by geography, memory, and survival.

Birds in Hand: Learning Science with Care

Handling birds during ringing sessions was humbling.

Measuring beak length, wing chord, and tarsus length taught me how millimetres matter. Each data point contributed to understanding migration, habitat preference, and population structure.

Ringing was especially powerful. A small metal band — engraved with BNHS — transformed into a passport. A promise that this bird’s journey mattered enough to be remembered.

Beyond names and numbers, the birds taught quieter lessons:

Resilience — crossing continents guided only by instinct

Adaptation — thriving in ever-changing landscapes

Interconnectedness — how wetlands, people, and birds are inseparable

Field ornithology trains your eyes, but it also recalibrates your mindset. You return more observant, more patient, and deeply respectful of natural systems.

Understanding Birds Beyond the Field Guide

Colour tags allowed identification without recapture. Metal rings connected birds to global databases. Telemetry devices revealed invisible flight paths through solar-powered signals.

Watching centuries-old migratory instincts pair with modern technology felt surreal. Science didn’t diminish wonder — it deepened it.

Safe handling and initial observation

Good enough to prevent injury, gentle enough to reduce stress. Before any data is recorded, the bird is calmly observed for:

Overall condition

Plumage details

Beak shape and length

Behavioural cues

This moment reinforces the ethics of field ornithology — the bird always comes first.

Beak measurement

Measuring the beak length may look simple, but it is critical for:

Species confirmation

Age and subspecies differentiation

Understanding feeding ecology

It was fascinating to learn how millimetres matter — especially among sandpipers and plovers, where subtle differences define identity.

Wing chord measurement

Wing length helps researchers understand the age of the bird, and few more details. Seeing the wing fully extended reveals the engineering of flight — layered feathers designed for endurance, speed, and efficiency.

Tarsus and leg measurement

Leg measurements tell quiet stories:

Habitat preference (mudflats, shallow waters, grasslands)

Wading depth adaptation

Foraging strategies

At Point Calimere, these measurements made perfect sense when later observing birds feeding in tidal wetlands.

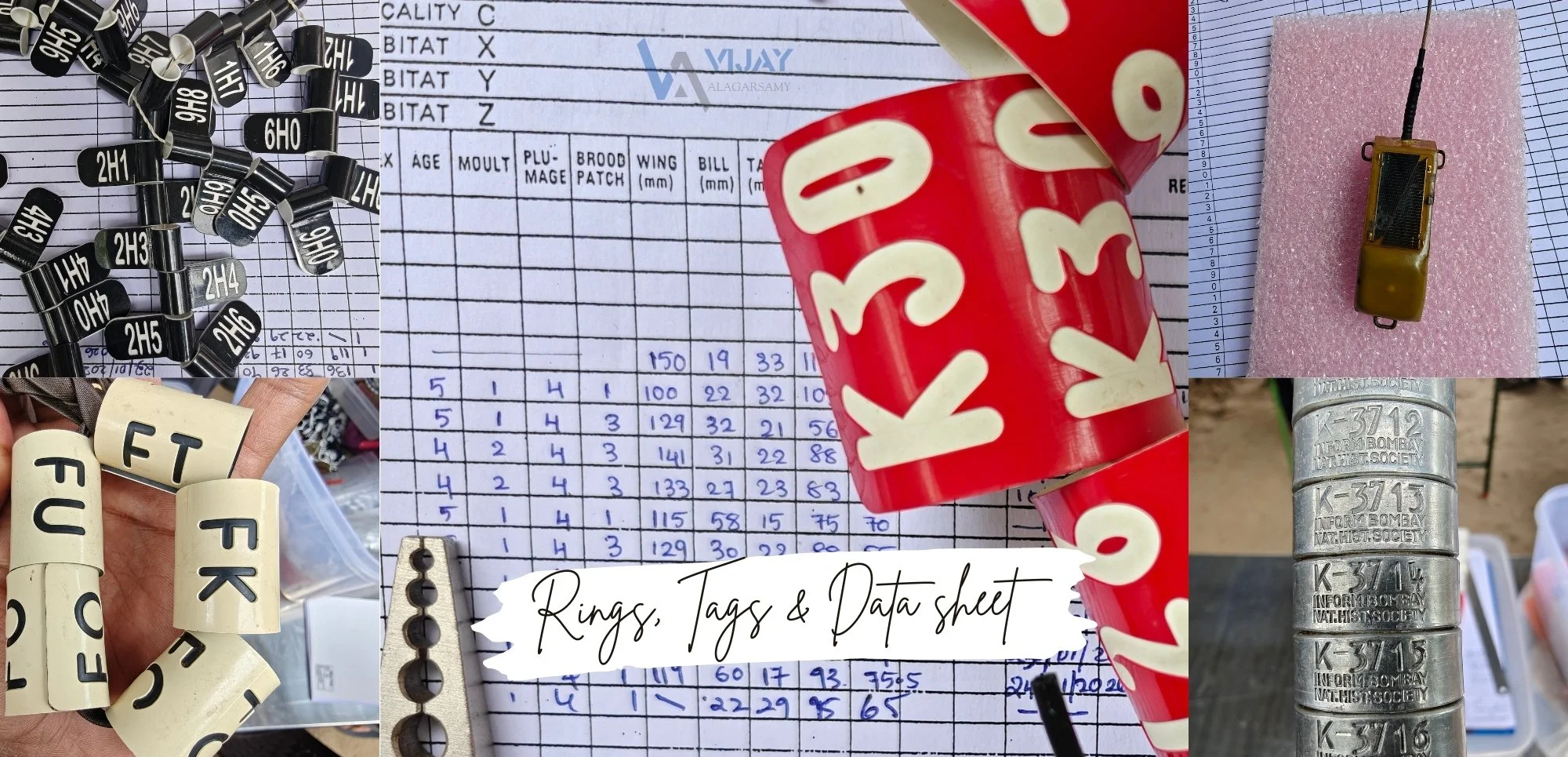

When a Ring Becomes a Story: Ringing and tagging

Perhaps the most humbling part of the process.

Each ring is a passport — a tiny metal band that connects this bird to a global database. Someday, somewhere else, this same bird may be recorded again, telling a story of migration, survival, and distance covered.

At that moment, conservation felt deeply personal.

The brilliance of birds — whether it’s a sandpiper, plover, Brahminy Kite, or a quiet bulbul — lies not only in their beauty, but in their ability to connect continents, ecosystems, and people.

Bird rings and coded leg bands

These small metal and plastic rings may look ordinary, but they are anything but. Each ring carries:

A unique identification code

The mark of BNHS, linking the bird to a global scientific network

The potential to be read again — weeks, months, or even years later — somewhere far away

At that moment, it struck me:

A bird’s entire migratory life can be traced back to this tiny circle around its leg.

Colour-coded tags

Colour tags add another layer to migration studies.

They allow:

Identification without recapture

Tracking movement within local landscapes

Quick recognition through binoculars or cameras

It felt incredible to learn that a bird feeding quietly in a salt pan could already be a known traveller, carrying a visual identity visible to researchers across regions.

Metal Rings and Global Connections: BNHS metal rings

Seeing the engraved rings up close — stamped with Bombay Natural History Society — was deeply grounding.

These rings are:

Standardised

Internationally recognised

A bridge between Indian wetlands and global migration databases

Each number is a promise that the bird’s journey matters enough to be remembered.

Transmitters and antenna tags

Perhaps the most futuristic part of the course was learning about telemetry devices.

These tiny transmitters:

Are lightweight and carefully designed

Send signals that help track movement over long distances

Reveal stopover sites, flight paths, and habitat use

What amazed me most was the contrast —

a centuries-old migratory instinct paired with modern solar-powered technology.

Data Sheets: Where Observation Becomes Conservation

And finally, data sheets. Quiet, unassuming, yet foundational. Conservation is built not on single sightings, but on patterns revealed over time.

Field data sheets

Every measurement, ring number, and observation eventually finds its place here.

These sheets represent:

Hours of patient fieldwork

Consistency across years and locations

The foundation for conservation decisions

It reminded me that conservation isn’t built on single sightings —

it’s built on patterns revealed over time.

At the Site: Living Simply, Learning Deeply

Tent life was comfortable, grounding, and honest. Food was nourishing and timely. But the real richness came from the knowledge-filled sessions — thoughtful, accessible, and deeply rooted in field experience.

There was no hierarchy, only shared curiosity.

What Point Calimere Gave Me

This journey reshaped how I see birds — and landscapes.

Forests, salt pans, wetlands, and lighthouses may seem unrelated at first glance. But at Point Calimere, they form a single ecological narrative.

Birds don’t see boundaries the way we do.

They move fluidly — forest to coast, salt pan to mudflat, land to sea.

This journey taught me that conservation cannot be fragmented. To protect birds, we must protect entire landscapes, histories, and the quiet spaces in between.

It feels fitting that everything began with a ride to something called the Kuruvi office.

As the course concluded, I realized I wasn’t leaving with just notes and checklists — I was carrying a renewed sense of responsibility.

To observe is to care.

To count is to protect.

And to learn is the first step toward conservation.

Grateful to BNHS, the wonderful researchers/mentors at the BNHS - Bird Migration Study Center, fellow participants, and the living classroom that is Point Calimere — this journey has only strengthened my bond with birds, wetlands, and the quiet power of nature.

This is not the end of learning — it’s the beginning of watching the skies with intention.

Disclaimer

This blog is a personal reflection based on my learnings, observations, and experiences during the field ornithology and bird migration studies at Point Calimere. The interpretations shared here reflect my understanding at the time of writing. If any aspect of migratory studies, bird behaviour, or conservation science is represented differently or requires correction, I sincerely welcome your feedback. Please feel free to share your insights through the comments or reach out to me via email. Learning, after all, is always ongoing.